What are hotshots, and who were the 19? Some choose to share history or stories through avenues such as movies, plays, books, museums, and even art. By creating this mural, the goal is to answer the above question, give reverence to the men who heroically gave their lives to save ours, as well as honor the men that continue to put their lives on the line to protect us today.

Intro

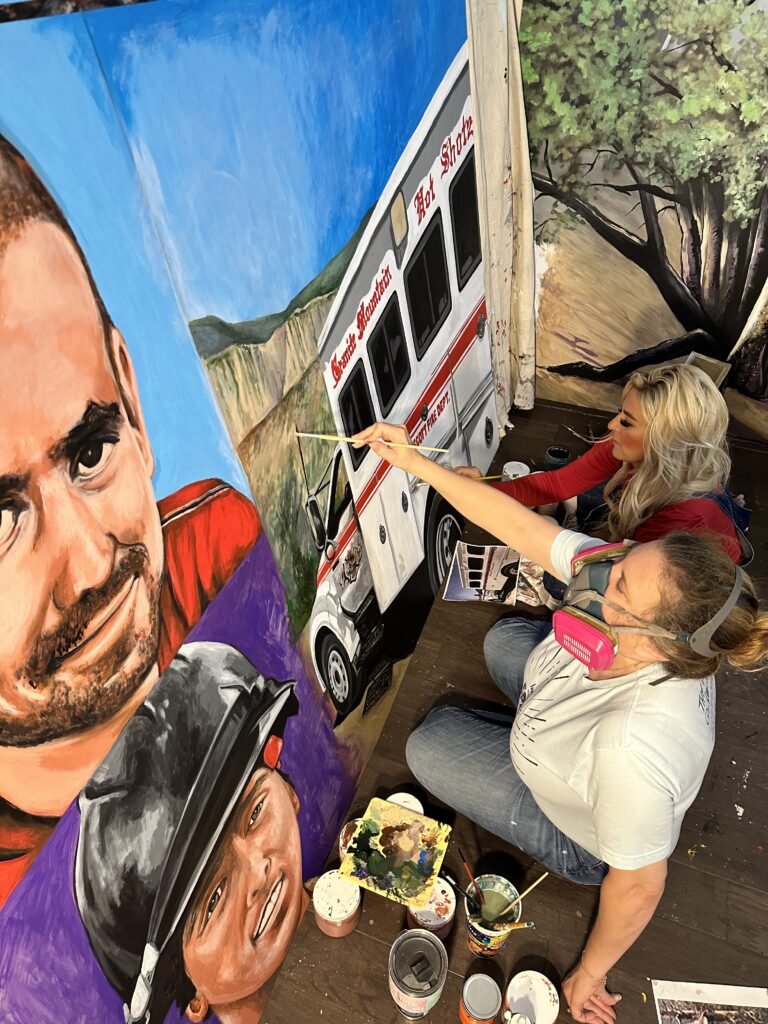

This collage-style mural makes up 462 square feet of acrylic-painted artwork, created on 11 separate aluminum panels. These panels are installed here on the exterior walls of the historic Prescott Chamber of Commerce building, which used to be a firehouse and jailhouse in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The artist chose to paint the mural on panels instead of directly on the wall for several reasons. First, this decision aimed to preserve the integrity of the historic Chamber of Commerce building. Additionally, by using panels, the mural could be easily removed if the adjacent lot underwent development, rendering the artwork unviewable. Moreover, this approach allowed for the flexibility of breaking up the mural into different sizes and reinstalling it in various interior or exterior locations if needed. The mural itself serves as a visual representation of what it means to be a Hotshot while specifically commemorating the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots who tragically lost their lives battling the Yarnell Hill Fire. It encompasses a wide range of elements, including their actual portraits and names, their fire station, helmets, tools, and buggy. It also features the sacred historic Juniper tree they saved, the dropping of slurry, the fence of gifts, the map of the meticulously crafted Memorial Trail, as well as their motto and quotes from Superintendent Eric Marsh’s “Who We Are” letter.

Upper left side panel

The first panel of the mural presents a vibrant, colorful, and stylized representation of Granite Mountain at sunset, incorporating hues that evoke fire. Positioned at the center of this panel is the Granite Mountain Hotshots logo. The concept for this panel draws inspiration from a banner that hangs in the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew Learning and Tribute Center. The banner serves as a tribute, displaying the names of each fallen Hotshot, emphasizing that they will be “Forever in Hearts” and “Gone but Not Forgotten.” This mural serves as another powerful testament to how the 19 will be forever honored and not forgotten.

Middle left side panels

The upper left-hand corner is a visual portrayal of Fire Station 7, where the hotshot team was initially interviewed, hired, and trained to be hotshots. Directly below, the mural depicts the Alligator Juniper Tree, which the hotshots saved on June 16th, 2013. The Alligator Juniper is said to be the state’s oldest living icon, estimated at approximately 1400 years old. Thanks to the 19, this national co-champion alligator juniper was rescued. They ascended the mountain, cleared dense vegetation around the tree’s base, and created a fire line just two weeks before the tragedy. Adjacent to the tree, there is a depiction of the logbook or “journal,” complete with the signatures and recorded entries from many of the crew who undertook to save the tree that day.

The Hotshot Trail Map is also included in the middle of this group of panels. The Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park was dedicated in 2016 as a place of remembrance for the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshot Firefighters who were lost on June 30, 2013, while fighting the Yarnell Hill Fire. This 2.85-mile trail hike to the observation deck provides a better understanding of the experience of these men as well as a view of the beautiful town of Yarnell and the surrounding areas. Every 600 feet, one of 19 plaques is set into rocks, sharing a photo and a story of each fallen Hotshot. There are also four interpretive signs paired with memorial benches that provide information about wildland firefighting. Further down on the Memorial Trail, you can pay your respects at the site where the Hotshots were recovered. The hike is approximately 3.5 miles long from the trailhead to the Fatality Site.

Next to the map, there is a portrayal of a slurry. A slurry is a mixture of water, fertilizer, and chemicals that is dropped from planes, which is a bright red color, making it visible for aircrews to track where they have previously dropped. Slurry is used on specific areas to slow a fire’s advance, allowing crews to get into an area to build hard lines or fire breaks. There is also a depiction of a non-specific Hotshot here, looking up at the slurry, illustrating what their helmets looked like.

Lastly, in this arrangement of panels, the artist included some of the tools used by the hotshots in fighting wildfire. The tools used each time vary depending on what the fire and terrain demands. The hotshots carry 40-pound packs with these tools on their backs while hiking through rough terrain and sawing down brush. One of the tools, a Pulaski, which is a special hand tool used in wildland firefighting, combines an ax and an adze in one head, with a rigid handle made of wood, plastic, or fiberglass. A Pulaski is a versatile tool for constructing firebreaks, as it can be used to both dig soil and chop wood.

Painted next to the Pulaski is the fire rake, which is used to quickly clear pathways while chopping and raking underbrush weeds and vines. Also included in the group of tools here is a chainsaw. The chainsaw is used to clear fire lines and remove hazardous trees or snags. On every hotshot crew, there are 2-3 saw teams of two people, people who are trained and qualified (certified) to cut down trees with chainsaws amid wildland fires. In addition, on every hotshot crew, there are 2-3 hotshots that carry drip torches. The drip torch, painted last in the group of tools, is an effective tool used for wildfire suppression, controlled burning, and other forestry applications to intentionally ignite fires when needed.

Lower left side panels

On the lower left side of this group of panels is a large painting of a handful of the 19 hotshots overlooking the mountain and smoke. This painting was created from an actual photo and is used to show the men at work without seeing their faces. By depicting their backsides only, the artist chooses not to highlight any one of them more than the other in the mural to ensure that each hotshot receives equal amount of reverence.

In this assembly of panels, you will also see a reference to the Arizona state flag but with a flame in the middle instead of a star. This section of the mural was inspired by a small poster at the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew Learning and Tribute Center that signifies fire prevention. Although these hotshots lost their lives tragically because of a fire started by lightning, it is very important to the families that fire prevention continues to be stressed as we honor the hotshots’ legacy. To practice fire prevention, it is important to create clearings where all flammable materials have been removed and keep sparks away from all dry vegetation. Thick brush and crowded trees can lead to uncontrollable wildfires. According to the Four Forest Restoration Initiative, an estimated 74% of our state’s forests are overgrown and in need of management. Without action, uncontrollable wildfires put residents at risk and firefighters’ lives on the line.

The final section in this group of panels is the painting of the fence of gifts. This fence of gifts around the fire station was estimated to be 50-60 yards long, 7-8 feet high, and maybe as long as a football field when arranged together. The items shown here are representations of the thousands of items left at the fence, including flowers, almost 1200 T-shirts, posters, and artwork that families and students created. The fence of gifts shows only a sliver of how people all over the world, other hotshots and firefighters, and the community of Prescott and Yarnell came together to grieve and honor these brave men. It is noted that the community worked tirelessly to preserve the more than 9,000 emotionally laden items so that others could realize the impact the tragedy had on the community and beyond.

Middle panels

The middle panels are carefully painted portraits of each of the 19 fallen hotshots. Each is 30 inches by 30 inches, and they are placed in no specific order. These are the names in order on the mural (from top left to right): Anthony Rose, Andrew Ashcraft, Scott Norris, Travis Carter, Dustin DeFord, Clayton Whitted, Kevin Woyjeck, Travis Turbyfill, Christopher MacKenzie, Sean Misner, Jesse Steed, Garret Zuppiger, Grant McKee, Robert Caldwell, John Percin Jr., Wade Parker, William Warneke, Joe Thurston, Eric Marsh, and Brendan McDonough.

The 20th hotshot here, the one with the purple background, is Brendan McDonough (“Donut” as his brothers called him). The artist used the purple background behind McDonough for two reasons: so that he would be set apart as the sole survivor and because purple is the color that represents wildland firefighters. The artist felt it important to include McDonough in the mural because he too is a hero. Since surviving the loss of his brothers, McDonough has become a public speaker and works with numerous nonprofits that support veterans, police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical services. His courage to find support at his weakest moment has inspired others to find their tribes of support. Building a sense of brotherhood within communities gives McDonough great joy because it allows him to honor the legacy of his 19 lost brothers.

Looking at the bottom right-hand corner of the portraits, there is a painting of one of the hotshots’ fire trucks, which they called “buggies.” The hotshots traveled both locally and nationally fighting wildfires in two buggies, a superintendent truck, and a chase truck. While the buggies and pick-up trucks were used to store and transport equipment, tools, backpacks, personal gear, fuel, and drip torches to and from wildfires, they were also the place where the hotshots slept, told jokes, listened to music, and bonded. Also in this segment of the mural are the words “Esse Quam Videri,” a Latin phrase meaning: “To be, rather than to seem.” This was the motto for the hotshots, which speaks to their commitment to genuineness and integrity: “Don’t pretend to be something that you are not.” The buggy and this motto were two things that all the hotshots shared and is the reason for including these items in this section of the mural alongside their portraits.

Far Right Panel

The very last panel on the right-hand side depicts the American flag with the wildland firefighter purple stripe and the number 19, with 19 stars in the usual blue area of the American flag. Also, inspired by banners and merch at the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew (GMIHC) Learning and Tribute Center, the artist added small excerpts from Eric Marsh’s “Who We Are” letter. According to Darrell Willis, former Division Chief of the Prescott Fire Department, this letter was written because superintendent Eric Marsh wanted to share the story of the GMIHC and get the city’s approval for the Hotshot team and funding.

The Full Rendition of the “Who We Are” Letter:

“Who are the Granite Mountain Hotshots? This is a simple question with a complex answer. We are many things to many different people.

To our peers, the 111 other Interagency Hotshot Crews in the nation, we are an oddity. In a workforce dominated by Forest Service and other federal crews, we have managed to do the impossible; establish a fully certified IHC program hosted by a municipal fire department. As remarkable and hard-won as this achievement is, we are odd for other reasons, too. We look different. Not because our buggies are white instead of green, but because we smile a lot. We act differently. We are positive people. We take a lot of pride in being friendly and working together, not just amongst ourselves, but with other crews, citizens, etc. We are problem solvers. We like to show up to a chaotic and challenging event, and immediately break it down into manageable objectives and present a solution. Quite often, we solve problems for people that they don’t even know they have. These things are possible because our folks are smart, motivated, and highly trained professionals that don’t see any task as “beneath” them.

To our city coworkers, we are a bit of a mystery. Guys that work in the woods a lot. We are nice, professional, and can assist many different departments with all manner of tasks. We show up when it snows, when something needs to be moved or set up, when it floods, when there are fireworks, when something needs a chainsaw. Most folks might not know we’ve been around for almost 12 years. Our first six years were spent in a building that had no heat or bathrooms, but lots of squirrels and mice. We didn’t complain too much, we just accepted it as necessary in order to fulfill our crazy dream of someday being a hotshot crew. We do a lot of fuels management, both on private property and city owned open space. We use chainsaws to cut the vegetation and then physically drag it to a chipper. It’s loud and dusty. This is a daily occurrence unless we are fighting fire or bad weather. We lead the nation with our fuels management program, having accomplished more than anyone else.

To our families and friends, we’re crazy. Why do we want to be away from home so much, work such long hours, risk our lives, and sleep on the ground 100 nights a year? Simply, it’s the most fulfilling thing any of us have ever done. It is difficult to explain the attraction of such a demanding job. We can show our wives and girlfriends pictures or videos, recount events and tell stories, but we all invariably receive the same blank stare and the obligatory “that’s nice sweetheart” response. It’s not because they don’t care. Our families are the most wonderful, supportive people in the world. It’s just difficult for anyone to grasp the magnitude of suffering and joy that we experience during a given fire season unless you have been there yourself.

To each other, we are chameleons. On the job, we are workers and supervisors, from no experience to 19 years of ‘hotshotting’ all over the country. Some of us are highly skilled with chainsaws; some have the stamina to swing a hand tool all day. Many of us have lots of experience with helicopters. When on a fire, we average 16 hours a day on shift, every day, for two weeks. We may hike with all of our gear for one to two hours before we get to our piece of fire line where we will start work. We don’t have bathrooms or showers and we eat a lot of bad food. We love it. Off the job, we are husbands, fathers, and boyfriends. We are cowboys, hot rodders, rock climbers, hunters, marathoners and bicycle racers. Due to our work, we have to fit a year’s worth of normal life into a six-month period during our winters. It really makes us appreciate the time with our families and pursuing our hobbies.

Maybe to answer the question of who are we, it would be helpful to explore who or what we are not. We are not nameless or faceless, we are not expendable, we are not satisfied with mediocrity, we are not willing to accept being average, we are not quitters.

Is this an all-inclusive answer to the question of who are we? No. Hopefully this is at least a beginning. We are approachable and we have no secrets. We are proud and passionate about our program. These things will show through during a discussion with any of our crewmembers. We don’t just call ourselves hotshots, we are hotshots in everything that we do.”

Conclusion

This mural serves as a tribute to our heroes, particularly the 19 fallen Granite Mountain Hotshots. Its purpose is to preserve their legacy, inspire you, and to therefore ensure that you take away at least two valuable lessons: Don’t pretend to be something that you are not (“Esse Quam Videri,” their motto) and be a “hotshot in everything that you do.”